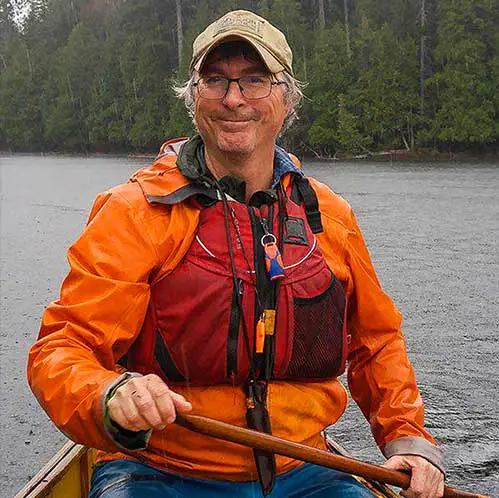

My passion for canoeing began at the age of twelve. My father and I were at a remote fishing lodge in Ontario’s Algoma Highlands and spent a good part of the week trolling the main lake without much luck. The second-last day, we decided to borrow one of the lodge’s beat-up aluminum canoes and portaged into a neighboring lake to try for speckled trout. We caught plenty of fish, but it was the idea of the canoe itself taking me to such a special place, a place that truly characterized remote wilderness, that I was hooked on. I’ve yet to look back. At the age of 55, I’ve never had a full-time job; and most of the jobs I have worked at had something to do with paddling wilderness areas and casting a line. It’s a dream come true

The canoe is still my choice for getting around out there. It’s the one thing that definitely binds me irrevocably to the wilderness. I even find the motion of paddling the craft itself very methodic; the action of drifting across a calm lake or being pulled downriver is very Zen-like..

My passion may have something to do with the fact that I’m Canadian as well. Even though canoeists owe a great deal to Scottish philanthropist, John MacGregor, who popularized canoeing as a recreational sport back in 1865 across Europe and the United States, I doubt few would argue that the Canadian identity itself lies with the canoe. After all, if Canadian film producers ever wanted to depict the opening of Canada’s wilderness the way Hollywood characterized winning the Wild West, the hero wouldn’t be straddling a horse, but rather crouched down in a canoe, paddling off into the sunset. The packsack, paddle, and portage are as much pioneer icons as the chuckwagon, boot spur and ten-gallon hat. Maybe the closest this aspect of Canadian culture has come to be represented in film (the work of Bill Mason excluded) is with the Frantic’s Mr. Canoehead, a superhero who had his head inadvertently welded to his aluminum canoe by a stray lightning bolt.

To me, when I spot a car barreling down the highway with a canoe strapped to its roof, I don’t necessarily see a somewhat inexpensive recreational watercraft owned by some poor fool who can’t afford a speedboat; I see a way of life.