Presented by Garmin

Spring is an exciting time to be an outdoorsman in Canada, as fishing seasons begin to open, turkeys start gobbling, and the water and woods return to life after the long winter.

Unfortunately, this return to life also means the reemergence of one of the most discussed parasites that now call our country home – The Black Legged Tick.

So to prepare you for another tick season and to ensure you can enjoy your favourite hobbies with peace of mind, here are 10 key things to know about ticks from our conversation with one of the world’s leading tick and Lyme Disease researchers, Dr. John Aucott.

1) Where did it all start?

Lyme disease was first discovered in the town of Lyme, Connecticut when a group of children in a small area began experiencing symptoms reminiscent of Rheumatoid Arthritis.

After further evaluation of the cases, Dr. Allen Steere was the first to make the connection to ticks, publicizing his findings in a 1977 paper in the journal of Arthritis and Rheumatism where he referred to the illness as Lyme Arthritis. It later adopted the moniker Lyme Disease after the town in which it was discovered.

2) Where does Lyme Disease come from?

Contrary to popular belief, Lyme Disease does not originate in ticks.

In fact, ticks are simply the middle man, (or “nature’s dirty needle” as Kathryn Maroun, former host of What a Catch referred to them as) passing along the diseases they pick up from other animals as they move from species to species.

In the case of Lyme, the virus begins in White Footed Mice, the primary vector for the Lyme-Disease-causing bacteria Borrelia burgdorferri.

3) What ticks carry Lyme Disease?

The primary tick of concern when it comes to Lyme Disease is the Black-Legged Tick, also known as the Deer Tick.

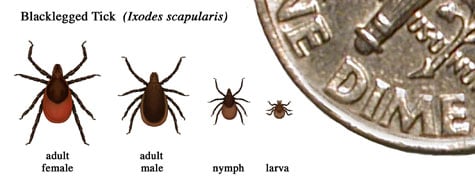

These ticks have 3 life stages but are perhaps most commonly encountered by humans in their Nymph and Adult stages where they can range in size from 1mm to 2.5mm.

4) When is prime tick season?

In our interview with Dr. Aucott, he emphasizes that his busiest time of the year is between May and July when the nymph-stage deer ticks are actively feeding. As shown in the chart above, ticks in this stage can be as small as a poppy seed and can easily be missed by those who are not actively looking for them.

5) How can you prevent a bite?

When we asked Dr. Aucott how we can prevent tick bites, he told us that the number 1 prevention tool is a substance called permethrin.

Permetherin is a natural derivative of the chrysanthemum flower that, when concentrated, kills ticks on impact. What is more amazing is that, unlike traditional DEET bug spray, this substance binds to clothing and does not make contact with the skin.

Unfortunately, despite its use to treat children with head lice and a long history of being used in Canadian military uniforms, the substance is currently banned for personal use in Canada due to concerns over bees and aquatic organisms. More on this can be found here.

Besides permethrin, tick bites can also be prevented using DEET bug spray and by reducing the amount of open-skin areas that the ticks can access. This can include tucking the cuffs of your pants into your boots or your shirt into your gloves.

When you get home, it is also important to do a thorough tick check and have a hot shower if possible. Throwing your clothes in the drier for 10 minutes or so will also provide enough dry heat to kill any lingering ticks.

6) How long does a tick need to be attached to spread the disease?

A tick bite does not necessarily mean you’re going to get Lyme Disease.

For starters, it is thought that ticks need to be attached for at least 24 hours before they can spread the disease and some reports put this figure up to 48 hours.

Furthermore, Dr. Aucott says that even if a tick is attached for this extended period of time, contracting Lyme Disease is far from a sure thing. “Depending on the region,” he says “the number of ticks that are actually carrying the disease can range from 0% all the way up to 50%.”

With these figures in mind, scientists estimate that the risk of contracting Lyme Disease after a tick bite falls somewhere in the single digits.

7) Why is Lyme Disease so hard to test for?

As Dr. Aucott alludes to during the podcast, Lyme Disease is hard to test for.

This is because testing currently relies on detecting the formation of antibodies rather than the bacteria itself.

“So you’re looking for the formation of antibodies,” says Dr. Aucott “and that relies on your immune system, and it takes several weeks, and it’s prone to the variability of your immune response. And not everybody makes antibodies like everyone else.”

8) How are we slowing the spread?

Slowing the spread of ticks is a bit complex due to their complicated life cycle but measures are being taken.

The adult stage ticks primarily feed on large mammals, such as deer, so population control in the form of hunting can often be a good way to slow the spread. As we have covered previously, Black Bears are also a great host to ticks and can spread them hundreds of kilometres each season.

To control the larval and nymph-stage ticks, permethrin-treated cotton is being used in some areas to provide White-footed Mice nesting material that will kill ticks on contact. Furthermore, vaccines are being explored that would make the mice immune to the bacteria altogether.

9) How far north can ticks survive?

Ticks are undoubtedly on the move and, unfortunately, very little of Canada is off-limits.

Dr. Aucott says that since ticks are frequently hitching rides on migrating animals such as deer, moose, bears, and even birds, there are not too many barriers to their spread deeper into Canada.

In positive news, this spread will likely come to an end once they reach the very far north, as the dry, arid climates of the tundra are some of the only places these ticks cannot survive.

10) Should ticks stop you from enjoying the outdoors?

Definitely not!

As Dr. Aucott reiterated throughout the podcast, fear of ticks should not keep you from enjoying the things you love. Even those in high-risk tick areas should still enjoy favourite outdoor hobbies, albeit with a little more caution and a couple of extra showers.

Want more tick info? In our latest podcast, Ang and Pete sat down for a full hour with Dr. Aucott and later, caught up with a good friend, Kathryn Maroun who has had her fair share of Lyme Disease experience. For the full episode, check out our podcast on Apple, Spotify, or wherever else you get your podcasts!

4 Responses

The more Info the Better.

And no Bullseye – the rash is more likely not to be the bullseye and just a longer lasting round or oval rash more than 2 or 3 inches..

You can buy permethrin in Canada it’s in fly spray for horses, Bronco equine fly spray has it and you just dilute it 😉

i bought this at a Urban Nature store. The one in Oshawa

https://www.urbannaturestore.ca/collections/pest-control/products/garden-protector-permethrin-spray-500ml-concentrate