Nearly every angler has had the experience of catching fish in their favourite spot one day and getting skunked the next. Many blame this on changing weather, fishing pressure, or luck, but very few ask whether the fish we target are actually learning from the catch and release experience. This question was put to the test in the late 1960s in a study known as the Pike Catchability Study (Beukemaj, 1970).

The Pike Catchability Study (Beukemaj, 1970)

The Pike Catchability Study was conducted by a research group at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, exploring the impact of angling pressure on game fishes’ ability to avoid baits and learn from the experience of catch and release fishing.

The researchers set out to measure the catchability of their most prominent local game species, Northern Pike, in a private pond over several days of controlled angling. The pond was stocked with 79 tagged pike with an average length of 48cm allowing all fish to be identifiable through each of the angling days in order to record the number of fish that were caught multiple times. The pond was fished for seven consecutive days by professional anglers, one group fishing artificial spinners, and the other fishing local live bait.

Results

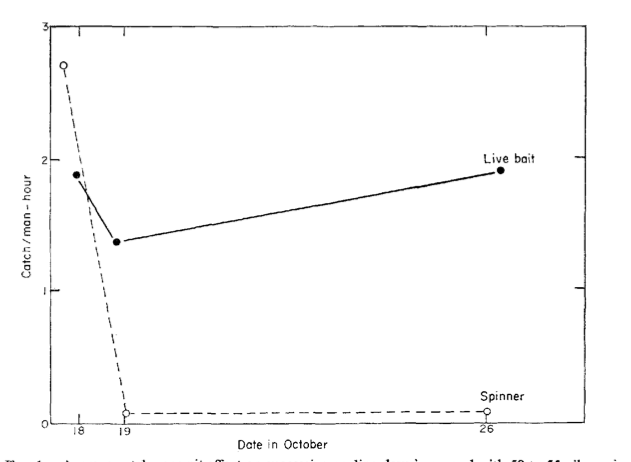

The results of the study showed that while artificial spinners were extremely successful on day one, even more so than live bait, the success on the same bait was reduced every day of consecutive angling and became virtually ineffective on previously caught fish throughout the latter days of the experiment.

Live bait, on the other hand, although less successful on day one, remained steadily effective throughout the entire study with no apparent change in effectiveness on previously caught fish (figure 1).

Explanation

The results of this study are rather significant and do seem to suggest that fish, Northern Pike, in particular, learn to avoid certain baits after being caught and released (Beukemaj, 1970). This phenomenon can likely be explained by the impact that both artificial and live bait have on the fish’s reward system (Beukemaj, 1970).

For example, fish are often attracted to artificial bait when there are no negative associations or experiences with the appearance of the specific bait. This connotation changes, however, once the bait is associated with a traumatic experience or pain, such as being caught, making the fish much less likely to eat the bait again, especially in the immediate future. This reward system is found everywhere in nature, explaining why animals tend not to approach bee hives or eat plants associated with pain or illness.

Live bait, however, appears to have much less of an impact on fishes’ reward systems due to the fact that it would be reset in between catches, as they would continue to eat these baits between catching periods.

For example, although an angler may catch a bass on a shiner minnow, the bass would have multiple opportunities to eat shiners again without this negative experience, resetting the fish’s reward system and making it very likely to eat this bait again.

Maximizing the effectiveness of artificial bait

Although this study showed how fast the effectiveness of artificial bait decreases over multiple fishing days, the experiment limited the anglers to only one bait and colour when fishing artificial spinners.

In fact, the study later showed that when even minor changes were made to the bait, such as the colour of the band around the spinner, the effectiveness of the bait was significantly increased (Beukemaj, 1970). This may explain why many stubborn anglers, both tournament and recreational, will struggle with baits that have known to work, while more experimental or unorthodox anglers will find success on unconventional baits and colours. This is especially true in tournament bass fishing as many anglers who had success in pre-fishing will struggle on tournament days when refusing to change trusted baits, resulting in slow and frustrating days on the water.

Tournament Fishing

This study may have further significance to tournament fishing, as the consecutive days of fishing artificial baits is essentially recreated in the tournament fishing platform.

In tournament situations, for example, many anglers will spend multiple days pre-fishing before a single or multi-day event in order to find spots and understand the body of water. This can often amount to nearly a week on the water, testing baits and methods each day while out fishing.

Based on the results of this study, this practice may not be as productive as it seems as the fish are likely to avoid these artificial baits come tournament time. This can be avoided, however, by pre-fishing with hookless baits, allowing the angler to figure out patterns without disturbing the target fish’s reward system.

Modern Artificial Bait and Fly Fishing

Although the results of this experiment are valid and have been reproduced for multiple game species, there are some flaws with the experiment that may make it less relevant to today’s anglers.

For starters, the experiment was conducted in the 1960s, well before the technology we see in modern fishing equipment was being incorporated into artificial tackle. The results of this experiment would be very interesting if completed today, using modern realistic soft plastics, for example, rather than spinners. It would be safe to hypothesize that modern soft plastics, with the look and feel of live bait, would have less of an impact on a fish’s reward system as the bait would be much closer to that of its regular food source than a shiny metal spinner, as seen below.

Another area of fishing not covered by this experiment is the use of artificial flies. Fly fishing compared to bait or gear fishing is very interesting in terms of its impact on the fish’s reward system as it seems to be unclear what the effect would be.

Based on this study, it would be relatively safe to assume that strange-coloured or unnatural-looking flies would likely have a similar impact as unnatural baits such as spinners, as the fishes reward system would not likely be reset between catch periods, while more natural flies would have much less of an impact.

This is something I have experienced personally while fly fishing for bull trout using flies that mimicked Kokanee flesh during the fall Kokanee spawn. I was able to land multiple good-sized bulls with white or red flesh-coloured flies while they preyed on the white and pink flesh of the dying Kokanee in the river. One fish, recognizable by the makings on its nose, was then caught again just four days later by a friend while fly fishing in the exact same run. Although the angling days were non-consecutive, this “coincidence” may suggest the lesser effect of realistic flies on these fish’s reward systems, or perhaps simply the aggression of predatory fish during times of heavy bait distribution such as an annual Kokanee spawn.