Walleye have nearly been wiped out in Golden Lake – but there IS a plan.

Don Bishop reminisces about the times when one could venture out onto Golden Lake and have a high degree of certainty of catching a walleye for dinner.

“We’d be pretty much guaranteed, 100 percent of the time, that we could catch walleye to eat,” said Bishop, who’s lived along the eastern Ontario lake for the past 35 years.

“[Now] you could fish hard all year, and you’d be lucky to maybe catch one or two.”

Until the late 1970s, the lake, situated approximately 150 kilometers west of downtown Ottawa, was regarded as one of the prime destinations in the region for the beloved game fish.

However, the walleye population witnessed a sharp decline in the 1980s and 1990s, leading to a temporary halt in walleye fishing from 2002 to 2007 to facilitate stock rehabilitation efforts.

Despite these measures, the numbers are still far from their historical peak. Nonetheless, Bishop, who boasts 25 years of experience in the aquaculture industry and currently serves as the co-chair of the Golden Lake Property Owners Association’s fish committee, has devised a plan to rejuvenate the lake. He is confident that this plan could also be applied to other areas with similar challenges.

A prized game fish, walleye was once abundant on the eastern Ontario lake. But the numbers have declined steadily since the 1970s.

The Problem

The issue doesn’t lie in the absence of walleye in Golden Lake.

As per Bishop and committee co-chair Peter Heinermann, the problem is that the young walleye hatching in the lake are generally too small to withstand the relentless predation from millions of significantly larger rainbow smelt.

“Smelt are voraciously carnivorous. And they love to eat the eggs and … the first-year offspring of most of the fish in the lake,” said Heinermann, A former member of the University of Ottawa’s biology department, holding a Ph.D. in fish biology.

Heinermann meticulously studied the annual fish stocking records for Golden Lake. His analysis revealed that the province predominantly introduced immature walleye into the lake, which included “eyed” eggs (embryos with visible eyes) as well as spring and summer fingerlings, small juvenile fish measuring just a few centimeters in length.

However, the year 1946 stood out as an exception. During that period, the province opted to stock Golden Lake with approximately 200,000 older, larger yearlings. These yearlings, measuring over 20 centimeters in length, were better equipped to withstand the presence of rainbow smelt.

Heinermann believes that this particular generation was able to firmly establish itself, ultimately giving rise to Golden Lake’s subsequent reputation as “the premier walleye lake in eastern Ontario.”

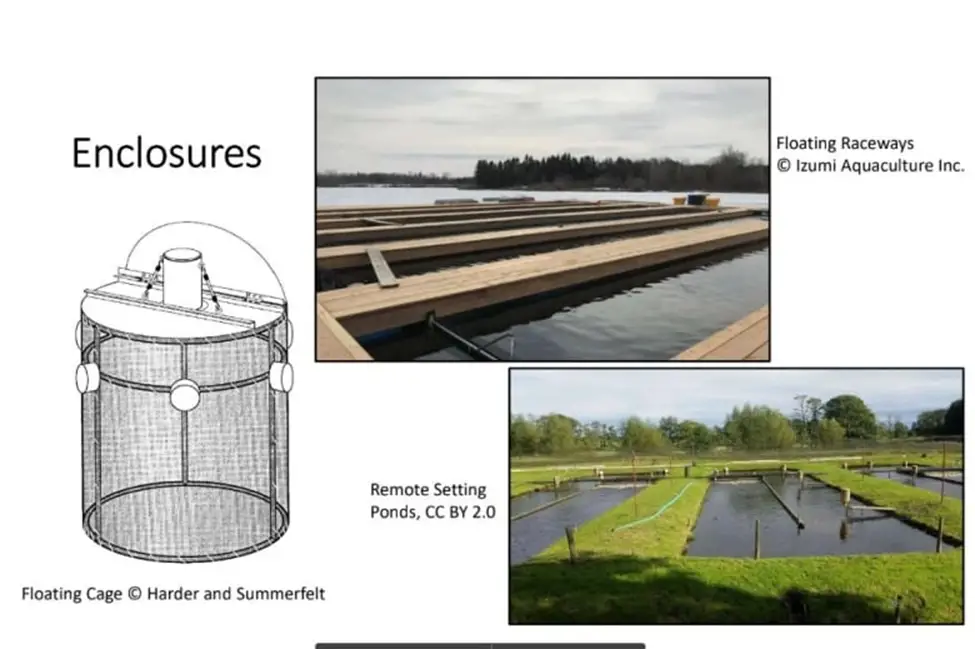

This slide from the fish committee’s public presentation in March 2023 shows designs for potential enclosures. (Golden Lake Property Owners Association Fish Committee)

The Plan

The committee’s strategy involves nurturing fingerlings in protective nursery cages during the summer. They will be cared for until they reach a point, much like the walleye of 1946, where they are sufficiently robust to confront predators such as rainbow smelt.

“Hopefully, by the time we get to the end of October, beginning of November, we get a fish that is as large as the smelt — but most probably larger — and won’t serve as [their] lunch,” said Heinermann. “It will be a serious competitor.”

They have formulated a five-year strategy for their efforts, as outlined by Bishop. This plan encompasses the construction and installation of outdoor cages, data collection, and the eventual establishment of an indoor nursery capable of producing mature fish for other lakes.

For this project, they have allocated an approximate budget of $350,000 and have officially submitted their proposal to the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

At left, several walleye summer fingerlings. At right, one significantly larger fall fingerling. (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Michigan Department of Natural Resources)

‘Seems to make sense’

Their plan has received initial endorsement from their neighbors, the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation, and their leader, Chief Greg Sarazin.

“Walleye has been a food staple for the Algonquin nation forever,” said Sarazin, who’s fished on the lake for decades.

“There’s still walleye there, but it takes a lot more effort. You don’t catch them the way you used to catch them,” he said. “I’m supportive of anything that might work. And the plan that they’ve laid out to us seems to make sense.”

John Yakabuski, the Progressive Conservative MPP for Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke, who held the position of Ontario’s minister of natural resources and forestry until 2021, also finds the plan to be logical and reasonable.

“The survival rate would go up exponentially for those fish,” said Yakabuski.

“It looks very good from the point of view of the ministry. It is a different way of doing things, so you’ve got to jump through some hoops, but we believe we’re on the right track.”

Don Bishop, left, and Peter Heinermann, right, cruise along Golden Lake in July 2023. They’re confident that if their plan proves successful, it can be applied to other Canadian lakes. (Trevor Pritchard/CBC)

‘A solution for all of Ontario’

One of the challenges involves obtaining the fingerlings from the province. Bishop mentions they are currently in a waiting phase, and there’s a possibility they may need to delay the launch until the spring of 2024.

The Ministry has acknowledged that various factors, including overfishing and habitat alterations, may have contributed to fluctuations in walleye populations in the lake over the years.

In more recent times, the ministry has introduced larger summer and fall fingerlings to the lake. These fingerlings are expected to possess the resilience necessary to withstand predation by rainbow smelt, as stated in the ministry’s communication.

“[We are] currently evaluating approaches to support a healthy walleye population and the greater fish community of Golden Lake and will continue to work with interested parties on any required applications,” the ministry said.

The ministry was asked if funding would be provided but did not offer up an answer.

Nonetheless, Bishop and Heinermann are confident that their plan holds economic merit. As Heinermann points out, fingerlings come at a low cost per fish. If their endeavor to rear young walleye to maturity proves successful, it may set a valuable example for other lakes to follow.

“Once we can demonstrate that [we can make it work], I think it will be a very favourable argument for using this approach elsewhere,” said Heinermann.

“We’re making a solution for all of Ontario,” added Bishop. “And I’m sure it can go beyond that, too.”