The St. Lawrence River is a familiar place to us here at Fish’n Canada. From pursuing trophy Smallmouth Bass to fishing and covering the Fish’n Canada Carp Cup, this river has certainly treated us well over the years. Despite our experience on the river, however, the vastness of this unique body of water always leaves more to be discovered. As many non-locals are surprised to learn, this waterbody famous for its freshwater sportfish also plays host to some of the most impressive marine species the world has to offer – including at least seven species of shark.

The St. Lawrence River:

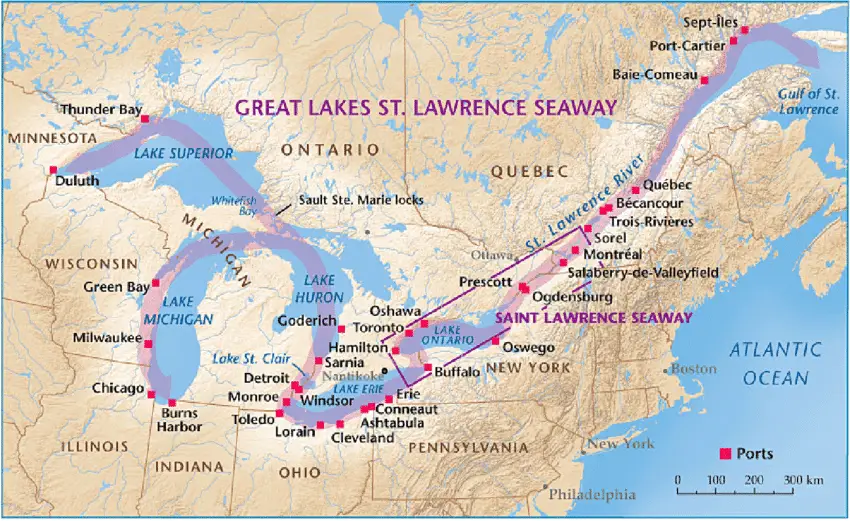

Before looking at the sharks that call it home, it is first important to look at the river itself. Sharks are, of course, saltwater species and, despite its reputation as a freshwater angler’s paradise, the St. Lawrence has plenty of it.

The true St. Lawrence River begins at the outflow of Lake Ontario and runs all the way through Quebec and eventually into the Atlantic Ocean. The waters of these two vastly different bodies of water meet just north of Quebec City at an island called Ile d’Orléans, where the freshwater of the Great Lakes and the saltwater of the Atlantic form a brackish river that gains in salinity as it flows into the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Flowing out of this brackish stretch of the St. Lawrence is the equally fascinating Saguenay River, which also plays host to a variety of marine life – including several species of shark. Roughly 93% of this unique river is composed of saltwater, however, nearly all of it is located in the immensely deep Saguenay Fjord.

The Sharks of the St.Lawrence

Though certainly common knowledge to many natives of Quebec, others are surprised to find out that the St. Lawrence River is home to healthy and sustainable shark populations. Here are a few of the ones that call it home:

Greenland Shark

Often referred to as the Bottom Shark by those who fish the St. Lawrence and Saguenay River, the Greenland Shark is perhaps the most prominent and unique shark that enters our waters. Living up to its nickname, these sharks prefer deep, cold waters – able to withstand depths of over 2000m (6,561 feet!).

The uniqueness of this shark, however, goes much further than the depths at which it swims. For starters, thanks in large part to their preference for frigid waters, much of what this shark does is extremely slow. From their average speed of 3km/h to their growth rate of just 1cm per year, these sharks truly aren’t in a hurry to do much of anything – and for good reason. Despite their slow growth rate, these sharks can reach massive sizes, growing up to 21 feet long. At a rate of 1 cm per year, that makes them the longest living vertebrate on the planet, capable of living over 640 years. For reference, this means that some of the sharks that swim our waters could have been born over 100 years before the time of Shakespeare.

Although their size may be intimidating, these sharks are of little danger to humans. In fact, despite being one of the largest carnivorous sharks in the world, no modern attack on a human has ever been confirmed. This, however, is likely more due to the shark’s preferred living conditions than any apprehension to foreign cuisine, as Greenland Sharks have been found to contain remnants of Reindeer, Moose, Polar Bears, and, according to the Florida Museum – a shipwrecked sailor’s leg.

Basking Shark

Growing up to 12 metres long, these sharks are by far the largest that enter the St. Lawrence and are the second largest, just behind the Whale Shark, to swim anywhere in the world. Most frequently spotted off of the Gaspé Peninsula, these sharks have become somewhat of a social media sensation due to their surface feeding activity and their tendency to look like massive, large-nosed Great Whites when viewed from above. Fittingly, the Basking Shark’s scientific name, Cetorhinus Maximus, translates directly to “Sea Monster with a Great Nose”.

Although Sea Monster may be forever rooted in their name, these sharks are harmless to both humans and fish, with plankton making up 100% of their diet. Despite this fact, however, the viewing of these sharks as angling competition, and the subsequent hunting as a result, has led to a significant decrease in their numbers on Canada’s western coast, making the St. Lawrence and the rest of the Atlantic Coast one of their strongest population centres (ORS).

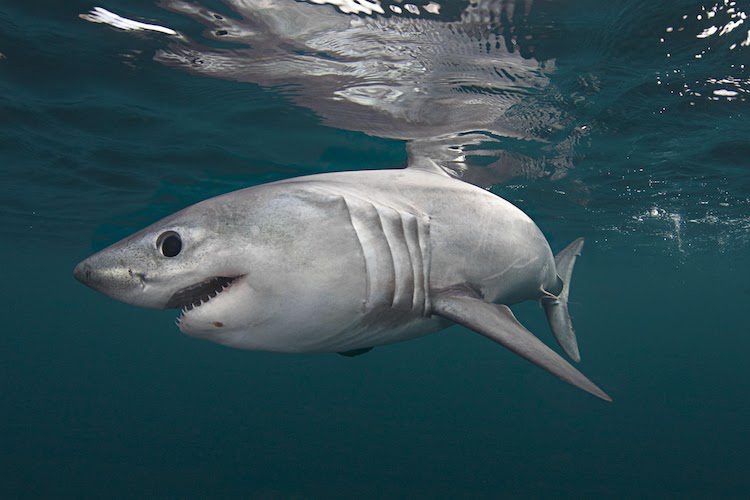

Porbeagle Shark

The Porbeagle Shark is another frequenter of the St. Lawrence as their preference for cold water and large bait draws them into the Canadian coast. Also known as the Salmon Shark, the Porbeagle is one of the fastest swimmers in the world, being a close relative of the Mako which reaches top speeds at 74 km/h.

Though perhaps lesser known than some of the other species on this list, the Porbeagle Shark is a fascinating and uniquely northern species. In fact, as suggested by The Ecology Action Centre, the Porbeagle may indeed be “Canada’s Shark”, as many of them spend their whole lives in our waters while travelling between the St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, and all through the arctic.

In 2008, our very own Pete Bowman gained some rare experience with these sharks when he accompanied a team of researchers in the Bay of Fundy. On this trip, Pete had the honours of catching the mighty shark and bringing it boat side, a process that took nearly two hours from hookset to landing. Once boat side, the researchers were able to cradle and tag the shark before releasing it back into the water unharmed.

Great White Shark

Could a shark article be complete without mention of the notorious Great White?

Indeed, the nearly 20 foot long super predator does swim the waters of the St. Lawrence – and it appears to be at an increasing rate.

As stated by the St. Lawrence Shark Observatory (ORS), a boost in seal numbers is likely causing an uptick in the numbers of Great Whites entering the St. Lawrence Gulf and River. Despite the concerning imagery that these massive sharks often bring with them, Great Whites in the St. Lawrence is far from a new phenomenon and is actually a sign that their populations are recovering from historical overfishing and bounty hunting.

Lake Ontario Bound?

The sightings of sharks in the Great Lakes have been disproven about as often as Bigfoot. However, in 2014, when a video surfaced of a man supposedly catching one, the questions surrounding this topic began to rise again. Although the campaign was eventually claimed by the Discovery Channel as a promotion for their upcoming Shark Week, the question still arises: could a shark ever enter the Great Lakes?

While this question may seem obvious on the surface, as Lake Ontario and much of the St. Lawrence are comprised entirely of freshwater, the claims do have some validity. For starters, roughly 43 different species of shark are capable of living in freshwater and do so in rivers all over the world. The most notable of these is the Bull Shark, which has shown the ability to travel far upstream in rivers as nearby as the Mississippi.

Thankfully for those who like to swim in Lake Ontario, Bull Sharks do not enter the St. Lawrence. In fact, even if they did, the waters of the northern Atlantic, and even Lake Ontario itself, are far too cold for this tropical shark to tolerate.

But is that case-closed? Or could one of the sharks already mentioned in this article have the ability to make the trek into the waters that so many of us call home?

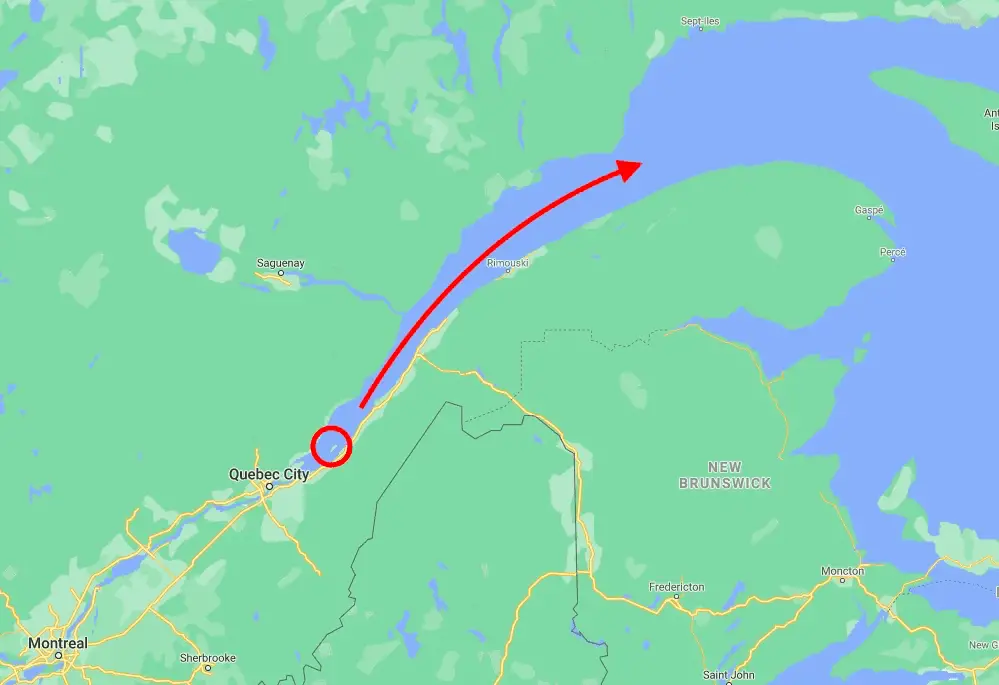

Starting with the question that is surely on everyone’s mind, the Great White cannot make it to Lake Ontario. Aside from its lack of ability to adjust to freshwater environments, this shark is yet another species that cannot withstand our harsh winters, appearing in the St. Lawrence only during the peak of our summers and leaving when things get a bit too cool for comfort. Despite their lack of ability to make it to our lakes, these sharks do get much closer than many are aware. As seen in the map below, the ORS has tracked all of the confirmed cases of Great Whites in the St. Lawrence and two of them are just hours from the shores of Quebec City. Although one of these confirmations was simply the finding of a recently shed tooth, the other shark was reportedly killed by a biologist in the late 40s – an event that surely made for quite the story at the time.

Another species that is frequently speculated to contain the ability to make it to our Great Lakes is the Greenland Shark. With its mysterious, deep-water nature and its rumoured tolerance for freshwater, could this be the shark to make it all the way?

Unfortunately not.

Opposite to the Great White, Bull, and other sharks on our list, the warmth of the Great Lakes, not the cold, is the primary inhibiting factor. For a species that prefers its environment colder than 42 degrees, the near 80-degree summertime highs in areas such as Kingston and Montreal are simply too warm to tolerate for these big arctic sharks.

Similar to the Great White, however, these sharks do get surprisingly close to populated centres in Canada, showing up frequently near Quebec City and throughout the Saguenay River.

Conclusion

The St. Lawrence River is a fascinating waterway, and although many of us will only ever enjoy its freshwater angling opportunities, there is something to simply knowing these creatures share the water with us that make these areas that much more enjoyable. While much of our shark-related media highlight the fascinating instances when these animals attack, it is always important to reaffirm that these events are incredibly rare and the future of our shark populations rely on the fear of these vulnerable animals turning into admiration.

Acknowledgement

The St. Lawrence Shark Observatory (ORS), mentioned at various points throughout this article, is Canada’s first Shark Research NGO and is the leader in researching the St. Lawrence’s unique shark populations. More information on their incredible work can be found on their website, along with interactive maps, videos, photos, and more.

References:

Canadian sharks – Sharks In Canada. (n.d.). Sharks in Canada. https://sharksincanada.ca/home/canadian-sharks/

Cetorhinus maximus. (n.d.). Florida Museum. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/cetorhinus-maximus/

Chavez, H. (n.d.). 9 Facts about the Greenland Shark. Oceanwide Expeditions. https://oceanwide-expeditions.com/blog/8-facts-about-the-greenland-shark

Gallant, J. (2021, April 30). White Shark. St. Lawrence Shark Observatory (ORS | GEERG). https://geerg.ca/en/white-shark/

Gallant, J. (2021b, June 10). Basking Shark. St. Lawrence Shark Observatory (ORS | GEERG). https://geerg.ca/en/basking-shark/

Greenland Shark Facts and Adaptations – Somniosus microcephalus. (n.d.). Cool Antarctica. https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/wildlife/Arctic_animals/greenland-shark.php

Marsh, J. H. (2006, February 7). St. Lawrence River | The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/st-lawrence-river

Porbeagle Shark. (n.d.). Oceana. https://oceana.org/marine-life/sharks-rays/porbeagle-shark

Porbeagle Shark. (n.d.-b). Nature Canada. https://naturecanada.ca/discover-nature/endangered-species/porbeagle-shark/

Rafferty, J. P. (n.d.). Greenland shark | Size, Age, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/animal/Greenland-shark

Rogers, M. (2016, June 9). Do Sharks Live In Freshwater? SharkSider.Com. https://www.sharksider.com/sharks-live-freshwater/

Somniosus microcephalus. Florida Museum. (2019, December 5). https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/somniosus-microcephalus/.

One Response

Great read Dean and some very interesting information on Shark behavior. I was especially intrigued with how far up the St. Lawrence and Saguenay Rivers these Sharks would travel in search of food. Salmonmay have definitely been on the menu. They may have also ventured into Lac St. Jean. Mother Nature has always been known to throw us a ‘high hard one’ or a ‘curve ball’ every so often. I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if they make their way up the St. Lawrence a bit futher. Sharks can be very adaptable creatures.