Catch and release fishing has quickly become the most dominant sector of the recreational fishing world, practiced as diligently on the rivers of BC as it is on the lakes of Wisconsin and on the loughs of Ireland. Although from the outside, with its stadium-filling bass tournaments and “grip and grin” photography, the practice often looks like little more than “playing with food”, the roots of the movement are as much in conservation as they are in sport and have been the driving factor in reviving many of our once depleted fisheries.

Despite its popularity throughout the west, catch and release has not risen to prominence without criticism and tensions are constantly rising as society continues shifting away from activities that fall under the “blood sport” banner. Though not yet facing the same scrutiny as the hunting industry, recreational fishing is not immune to similar treatment and animal rights groups, as well as entire countries, have begun targeting the once celebrated past-time.

The Past: The History of Catch and Release Fishing

“Our tradition is that of the first man who sneaked away to the creek when the tribe did not really need fish.”

Roderick Haig-Brown

Fishing, in general, has been around since man itself, but it was not until much more recently that the idea of fishing for recreation, rather than sustenance, was first introduced. While there is speculation that rod-bearing anglers of ancient Rome (see photo above) and Japan did practice aspects of modern recreational fishing, it was not until the late-1400s when fishing for the purposes of recreation first appeared in writing.

In Culture

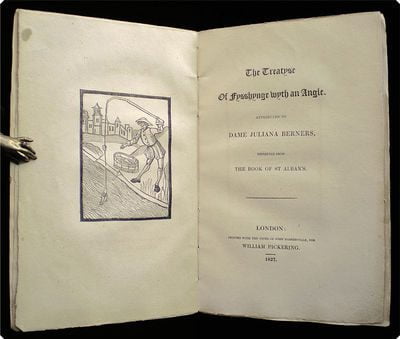

This first account of fishing for sport appeared in 1496’s A Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle by English prioress Dame Juliana Berners. In addition to introducing one of the most creative spellings of the word fishing (one that I hope makes a comeback), the last two pages of this treatise also identify, for the first time in written history, the non-consumptive value of fishing as an activity, stating its purpose as

“to serve a man for solace, and to cause the health of his body, but especially of his soul,”.

Later in this same section, Dame Juliana Berners also sets the framework for the modern catch and release philosophy, stating that,

“Nor should a man ever carry his amusement to excess, and catch too much at one time; this is to destroy his future pleasure and to interfere with that of his neighbours.”

She later ended the section with the first attribution of Trout (troughte) and Grayling (gryalynge) as “gamefish” and worthy of different treatment than other “vermin”:

“A good sportsman too will busy himself in nourishing the game and destroying all vermin.”

Running with the ideas laid out by Berners, recreational fishing was officially brought into the mainstream around 150 years later when Sir. Izaak Walton published his famous The Compleat Angler. Published in 1653, this legendary book laid out the first justification of angling as a sport, describing the spirit and art of fly fishing in a way that forever changed the public’s attitude towards fishing. Foreshadowing the modern fishing culture, Walton also laid out the etiquette of what he called “the civil, well-governed angler”, a concept alive and well (for better or for worse) in the modern fly fishing world.

Canada’s Role

Other than being one of the first countries to adopt the practice as a legal means of conserving fish populations, Canadian television also had a large role in introducing the idea of catch and release to the mainstream and Fish’n Canada was one of the leaders. Thankfully, the two hosts of the celebrated show work in the room right next to mine and I was able to talk to them about some of the earlier days of the catch and release movement.

“Back in 1983,” said Pete, “well before the catch and release phase of angling became a mainstay, Fish’n Canada’s Angelo and Reno Viola started preaching the words “Catch Your Limit But Limit Your Catch” across the nation via their television program. They knew they were in for an uphill battle with the old-school mentality of keeping a limit of fish every time out, but they stayed relentless. Today, the only fish you will see harvested on Canada’s #1 rated outdoor program, is the odd walleye or maybe a pike for shore lunch. Ang and I love an occasional meal of fish; with the emphasis on occasional.”

“Put simply, catch and release fishing would not be where it is today without Canadian fishing television in the 80s and 90s,” said Angelo.

“I remember our first trip to Canada’s west coast, early in Fish’n Canada’s history, I believe it was 1986,” he continued. “We were catching Chinook Salmon on the first day of our trip and releasing them back into the ocean. The guide was having a fit and couldn’t believe what he was seeing.

“The word soon got around camp that some crazy TV show guys were throwing away perfectly good salmon so orders were given to not put us on to fish for the rest of the trip and we didn’t see another fish the rest of the week. We were bound and determined that this wasn’t going to stop us from doing what we thought was the right thing. That season we successfully released 100% of the fish we caught and started total catch and release TV fishing.”

“Although fishing tournaments were instrumental in the introduction of the whole catch and release concept, with B.A.S.S. founder Ray Scott leading the way, it wasn’t until TV fishing shows started “putting them back” and talking about it to national audiences that the everyday anglers started taking notice. I’m also proud to say that Canadian fishing shows played a lead role in North American catch and release fishing.”

The Present:

In Law

Catch and release fishing may have entered the culture in the 15th century, but it was not until the conservation movements of the mid 19th century that it began to enter the legal arena.

Stemming from the ideas of American writers and thinkers such as Henry David Thorough and later Aldo Leopold, the 1950s’conservation movement in the United States saw the first use of catch and release fishing as a conservation tool.

The first example was seen in Michigan in 1952 when an effort to reduce trout stocking demands led to the creating of a “no-kill zone” – areas where all fish caught must be released. In addition to saving the government money by minimizing how often lakes had to be stocked, this also created the first precedent for fish being stocked, and caught, strictly for the purpose of fun.

Since the first legal use of the practice in Michigan, catch and release is now used globally as a tool for managing fish populations and is even mandatory on some sensitive waterways. In British Columbia, the province’s legendary salmon and steelhead fisheries are maintained with strict catch-and-release-only regulations. In the UK and Ireland, countless carp and trout fisheries have adopted the practice in response to growing angling demand. And all throughout Canada, the United States, Japan, and Australia, bass fisheries thrive to the point where fully touring tournament industries are able to operate on the back of the new practice.

The Future?

The Opponents of Catch and Release Fishing

Catch-and-release has become near synonymous with fishing throughout North America and the UK, however, the practice is by no means universal and is still an oddity in much of the world. As it was throughout the majority of human history, catch-and-release fishing is considered wasteful in many areas as the luxury of releasing freshly caught food has not yet been afforded. In other areas, the practice is simply considered cruel – a purposeless torture of wildlife purely for the purpose of human enjoyment.

PETA is perhaps the leading proponent of this claim and continues to be the loudest voice in the movement to shift society away from all activities that fall under the “blood sport” banner. Hunters have felt the wrath of this organization since its inception but, to fishermen, it’s relatively new and it has only recently begun picking up steam.

In fact, according to Ontario’s former Minister of Natural Resources, Jerry Ouellette, PETA has made it clear to the Outdoor Writers of America Convention that they are much more opposed to live release fishing than they are to hunting, as it encourages the repeated torture of an animal rather than just a one-off event. This sentiment continues in their articles where they highlight their view of the cruelty of fishing, describing catch and release fishing as “cruelty disguised as sport”, citing that,

“once fish are hauled out of their aqueous environment and into ours, they begin to suffocate, and their gills often collapse.”

PETA

Although these claims are obviously exaggerated and are rarely taken seriously here in North America, the question of humanity when it comes to catch and release fishing has had its proponents since the sport’s inception and has even influenced politics in a few notable countries.

The End of Catch and Release Fishing?

In 2009, Switzerland made angling headlines when they officially outlawed fishing without the intention of harvest. Not the first country to make this move, the ban was modelled after a similar law in Germany which banned the practice since the enactment of the Animal Welfare Act.

Updated in the 1970s but retaining its core principles, the modern Animal Welfare Act states “no-one may cause an animal pain, suffering or harm without good reason.” – this includes fish. As one would assume, fun, art, and sport do not qualify as good reasons to break this law and anglers caught fishing with such purposes in mind face the possibility of fines, license suspensions, and, in extreme circumstances, even jail time.

So what does this mean for catch and release fishing in North America?

Well, unless you’re planning on travelling to Germany or Switzerland, probably nothing for right now. But these bans, and growing support for ones like it, do have the ability to threaten the future of our fisheries, especially in a culture that amplifies the loudest and most adamant voices.

One Response

interesting